Military-Technical Transformation: Preparing an Index to Enable Comparative Research

Project

For three decades, military strategists have claimed that information superiority would increasingly minimize or even replace firepower through the application of advanced information technologies on the battlefield (sensors, computers, automation etc.) (Owens 2001; Arquilla/Ronfeldt 1997; Libicki 1996).

For three decades, military strategists have claimed that information superiority would increasingly minimize or even replace firepower through the application of advanced information technologies on the battlefield (sensors, computers, automation etc.) (Owens 2001; Arquilla/Ronfeldt 1997; Libicki 1996).

How this revolution affects the probability of international conflict or the effectiveness of peacebuilding is fiercely debated between political decision-makers and from within the scientific community alike. Critics point to moral dilemmas, the erosion of international law, the marginalization of democratic accountability mechanisms (for example with regard to drone strikes) and higher risks of unintended conflict escalation (Bergen/Rothenberg 2015; Sauer 2014; Kaag und Kreps 2014; Boyle 2013; Neuneck 2012; Schörnig 2011).

What is missing though is a comprehensive understanding of the driving factors of state investments in areas such as satellite sensors, drone technology or remotely-guided missiles. Given the large number of potential explanatory variables (see Mathers 2002; Terriff/Osinga 2010: 199-200; Giles 2014; Giles/Monaghan 2014; Laird/Mey 1999; Forster/Edmunds/Cottey 2002; Adams/Ben-Ari 2005; Farrell 2008; Gareis 2011; King 2014; Foley/Griffin/McCartney 2011; Thiele 2011) and, arguably, the confounding influence of more than a few other factors, there clearly is a need to supplement qualitatively gained knowledge through quantitative research designs.

Nevertheless, multicausal large-N studies cannot be conducted as long as we do not have a standardized measurement of the dependent variable, namely the timing and intensity of state investments in information technology-centric military equipment. The research project seeks to fill this critical gap.

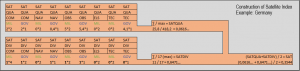

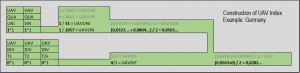

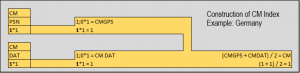

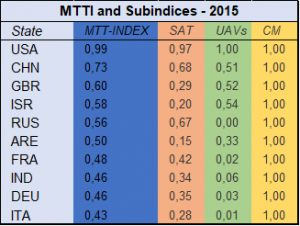

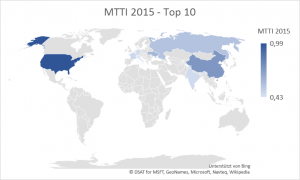

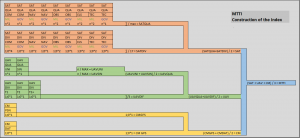

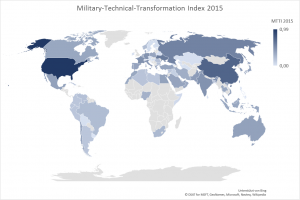

To this purpose, data about unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), satellites and guided missiles have been aggregated into an index that enables a standardized ranking of the capabilities of each state (see table).

The data availabaility issues and conceptional criteria that guided the selection of the indicators are explained in the ‚Research Aims & Conceptional Foundation‘ section. A detailed look at our data and a set of download options are provided in the ‚Data‘ section.

Amongst other things, our data can be used to plausibilize two different logics of military-technological diffusion:

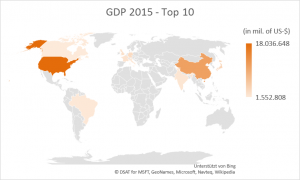

Structural-realist explanations of the military diffusion processes are based on the logic of systemic competition (Waltz 1979: 127) and a „technological imperative“ (Buzan/Herring 1998: 50-51; Resende-Santos 1996, 2007). Variances in military-technological capabilities result from the unequal resource bases (measurable in the gross domestic product) of different countries. Our data shows that, unsurprisingly, unequal resources clearly have some predictive power with regard to the military-technical capabilities. Yet other factors must play a role as well because the correlation is far from being perfect. A case in point are low MTTI-rankings of Latin American states with considerable economic resource bases (see „Data 2015“).

For illustrative purpose, see this comparison of the GDP and Index Value:

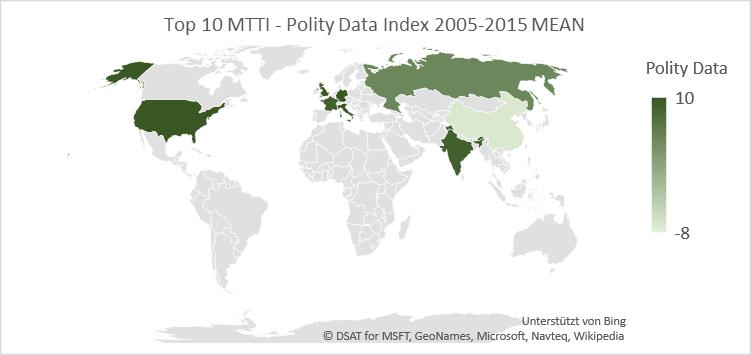

In contrast, liberal accounts of the ongoing military transformation, amongst other factors, point to the restraining influence of casualty-shy electorates on democratic security policy-making (Schörnig 2014; Sauer/Schörnig 2012: 371; Mandel 2004: 13-14). From this follow strong incentives to acquire precision-guided and automated military capabilities in order to minimize the death toll of military campaigns. Therefore, democratic regimes should be more eager to invest in satellite sensors, drone technology and guided missiles than their authoritarian counterparts.

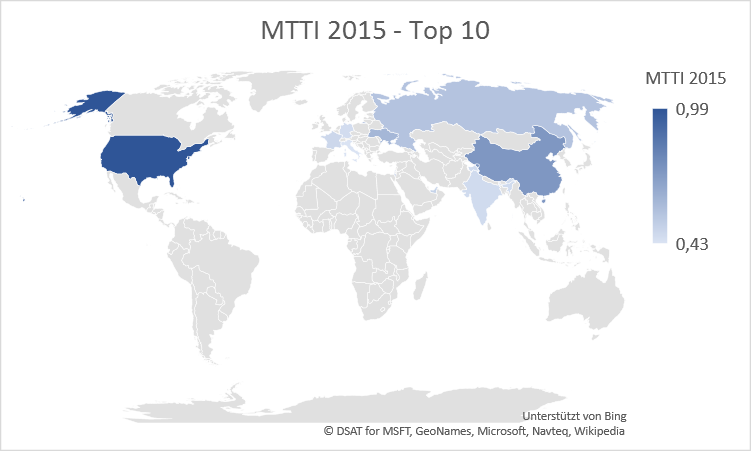

Our index, however, only partially confirms this logic. While there are indeed plenty of democracies (as measured by their Polity IV index scores) within top-rank positions, other democracies (for example Japan and, again, Brazil and Argentine) noticeably lag behind authoritarian countries of comparable size. What is more, small Arab autocracies such as the United Arab Emirates combine low Polity IV scores with leading MTTI positions (see „Data 2015“). The following picture shows some leading democracies and autocratic regimes as well as outliers.

Overall, these rudimentary plausibility probes lend support to the argument that we need to consider the influence of multiple factors and their interplay in contributing to top-ranking or low-ranking positions. One way to move forward is represented by the multivariate large-N studies, testing and assessing the relative explanatory power of a range of factors. Alternatively, a fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) would offer a way to identify specific combinations of factors that could each constitute a path to transformation leadership or low-ranking positions respectively. In the latter case, the numerical values of the index should be used to demarcate the categories of leaders, followers, laggers-behind etc.

Military-Technical Transformation: Preparing an Index to Enable Comparative Research

Research aims & Conceptional Foundation

While there is a popular narrative juxtaposing commercial entrepreneurship to change-resistant militaries and emphasizing spin-offs from civil information-technology to military systems only, in reality there seems to be a much more complex interplay of civil and military agency with regard to technological transformation and diffusion (Weiss 2014). Preliminary evidence also calls into question the simple idea of a „technological imperative“ (Buzan/Herring 1998: 50-51) that forces states to spend as much as possible on militarily effective and efficient technologies. In short, the causes of military investments are far from beeing self-evident and „politics matters“. Yet the causes of the recent military technical transformation are still underresearched as compared to the effects of some applications such as, for example, drone technology.

Against this backdrop, the research project aims at a better understanding of the driving factors of military investments in information-technology equipment. Different competing explanations – ranging from the regime type to security threats ((see Mathers 2002; Terriff/Osinga 2010: 199-200; Giles 2014; Giles/Monaghan 2014; Laird/Mey 1999; Forster/Edmunds/Cottey 2002; Adams/Ben-Ari 2005; Farrell 2008; Gareis 2011; King 2014; Foley/Griffin/McCartney 2011; Thiele 2011) – have so far been tested almost exclusively through a few qualitative case study designs. Methodologically, these studies focus on only a few, predominantly Western, countries. Furthermore, they do not necessarily clarify their case selection criteria. Our knowledge of the dynamics behind the military adaption and diffusion of information technologies is therefore not only limited but probably also biased towards relatively well-documented Western cases. A quantitative comparative analysis that includes cases from a non-Western context is needed in oder to alleviate these shortcomings.

source: istockphoto, Alexei Cruglicov

A necessary first step to fill this critical research gap is to generate and provide a standardized measurement of relevant military capacities. To that purpose, we have aggregated data about unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), satellites and guided missiles into an index that enables a standardized ranking of the capabilities of each state. Besides issues of data availability and quality (see ‚What we did and what we didn’t), this selection of technical indicators is based on the assumption that the disruptive potential of ongoing military-technical transformations is best captured by the concept of the OODA-loop (observe-orient-decide-act) (see Fadok 1997: 366). In particular, we argue that in military-strategic terms what is aimed for is both information superiority (radical improvement of information quantity and quality during the observe-orient phase) and shrinking time-lags between military decision-making and actions (the two latter phases of the OODA-loop). Theres is arguably a trade-off between these two goals as the quantity of technical intelligence can overwhelm human decision-making capacities and, thus, slow down or even paralyze military actions (Drew 2010). Militaries nevertheless tend so pursue both goals at once and the technological capabilities we selected are key to both strategies (for more details see the section on methods).

A first downloadable version of our index contains data from 2015 (see data). Later versions will succinctly be created for 2010, 2005, 2000 and 1995. Once finished, the military-technical transformation index as well as the three composite indices can be used for quantitative hypothesis testing as a supplement to qualitative research designs. Some rudimentary plausibility probes of the predictive power of regime-type and resource-based variables are illustrated in the introductory section. Our ranking will also indirectly benefit qualitative research by broadening the base from which to find theoretically relevant empirical cases („crucial cases“). Moreover, clusters of states (transformation leaders, followers etc.) could be identified and then used in a fuzzy-set qualitative content analysis. Thus, we hope to serve multiple methodological pathways and thereby contribute to a more comprehensive research agenda on the causes and drivers of IT-based military transformations.

A deeper understanding of the reasons why states invest in IT-centric military capabilities would enable us to identity new possibilities (for example ‚issue-linkages‘, changes in the architecture of arms control regimes, regional partnerships) that would stabilize preventive arms control efforts alongside improved technical procedures. For example, causal analysis might reveal that effective governance mechanisms necessitate the participation of crucial regional powers or regional organizations. Strengthening parliamentary control might be a further necessity in order to avoid conflictive international dynamics while leading to the success of conflict governance mechanisms.

Military-Technical Transformation: Preparing an Index to Enable Comparative Research

What we did & didn’t

Measuring military technical transformation poses wide-ranging challenges. This section is about these difficulties and the way we have tried to overcome them. We explain our selection of indicators, which data we used and why, as well as the procedures of data aggregation. In short, we inform about what we did and what we didn’t. Please do not hesitate to contact us, if questions remain.

Our index is altogether a composite of three technological indicators. Conceptual assumptions as a basis of the selection criteria as well as the criteria themselves are respectively explained below. In its final version, the index measures the quantity and diversity of satellites and UAVs, respectively. In addition, cruise missiles are considered an indicator of military technical transformation if they are able to receive GPS signals or enable remote targeting via datalinks. Our measurement considers only operable systems and not research & development because our focus is on usable military capabilities only. The only exceptions are technological demonstration satellite systems because in this case it is hard to make a clear division between R&D and application.

DATA

… WE USED …

… WE DIDN’T USE

WHAT WE DID IN DETAIL:

The final index is aggregated from the combined satellite index, UAVs index and missile index scores. On the left: our construction, on the right: the result.

Military-Technical Transformation: Preparing an Index to Enable Comparative Research

Data 2015, 2010, 2005

Our data is accessible on this page in two ways. You can either search within our tables or download the data you need. ‚MTTI_subindecies and Index 2005-2015‘ aggregates the results of our analysis.

The data you will find within ‚SAT‘ ‚UAV‘ and ‚CM‘ contains the sub-indices results, including evaluative comments and source information. If any questions about our methods remain, please do not hesitate to contact us.

Military-Technical Transformation: Preparing an Index to Enable Comparative Research

Literature

All references on this homepage are listed below plus additional titles we deem useful in the context of our research project. You can get our plaine citavi-file by contacting us.

Adams, Gordon; Ben-Ari, Guy (2005): Transforming European Militaries: Coalition Operations and the Technology Gap, Abingdon/New York: Routledge.

Alberts; Hayes, Richard E. (2003): Power to the Edge. Command and Control in the Information Age. Washington, DC: CCRP Publication Series.

Alberts, David S. (2003): Information Age Transformation. Getting to a 21st Century Military. Washington, D.C.: CCRP Publication Series.

Alberts, David S.; Garstka, John; Stein, Frederick P. (1999): Network Centric Warfare. The Face of Battle in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Defense University Press.

Arquilla, John; Ronfeldt, David (1997): A New Epoch – and Spectrum – of Conflict. In: John Arquilla/David Ronfeldt (Eds.): In Athena’s Camp: Preparing for Conflict in the Information Age, Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 1-20.

Arnold, Brian A.; Vitrikas, Robert P. (1992): Effects of Modern Technology on Airpower and Intelligence Support. Washington, DC.

Assistant Secretary of the Army for Acquisition, Logistics and Technology: Weapon System Handbook 2016. Washington, DC.

Beier, J. Marshall (2006): Outsmarting Technologies: Rhetoric, Revolutions in Military Affairs, and the Social Depth of Warfare. In: International Politics 43 (2), 266–280.

Bergen, Peter; Rothenberg, Daniel (Eds.) (2015): Drone Wars. Tranforming Conflict, Law, and Policy, (Cambridge University Press), Cambridge.

Boyle, Michael J. (2013): The Costs and Consequences of Drone Warfare, International Affairs, 89 (1), 1-29.

Buzan, Barry; Herring, Eric (1998): The Arms Dynamic in World Politics, Boulder/London: Lynne Rienner.

Defence Research and Development Canada (2010): Concept Development of Artillery Precision Guided Munitions. Accessed: http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a590120.pdf.

Dickow, Marcel et al. (2015): First Steps towards a Multidimensional Autonomy Risk Assessment (MARA) in Weapons Systems. Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik. Berlin (FG Sicherheitspolitik, WP No 05).

Drew, Christopher (2010): Military is Awash in Data from Drones, The New York Times, 11.01.2001, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/11/business/11drone.html (accessed: v11.02.2010).

Dworok, Gerrit; Jacob, Frank (Eds.) (2016): The Means to Kill. Essays on the interdependence of War and Technology from Ancient Rome to the Age of Drones. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc. Publishers.

Economist Intelligence Unit and Booz Allen Hamilton (2011): Cyber Power Index. Findings and Methology. Accessed: http://www.boozallen.com/insights/2012/01/cyber-power-index.

Farell, Theo (2008): The Dynamics of British Military Transformation. In: International Affairs, 84 (4), 777–807.

Fadok, David S. (1997): John Boyd and John Warden: Airpower’s Quest for Strategic Paralysis. In: Philip S. Meilinger (Eds.): The Paths of Heaven: The Evolution of Airpower Theory, Maxwell Air Force Base, AL: Air University Press, 357-398.

Foley, Robert T.; Griffin, Stuart; McCartney, Helen (2011): ‚Transformation in Contact‘: Learning Lessons of Modern War. In: International Affairs, 87 (2), 253–270.

Forster, Anthony; Edmunds, Timothy; Cottey, Andrew (Eds.) (2002): The Challenge of Military Reform in Postcommunist Europe, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Frank, Aaron (2004): Get Real: Transformation and Targeting. In: Defence Studies, 4 (1), 64–86.

Fukuyama, Francis; Shulsky, Abram N. (1999): Military Organization in the Information Age: Lessons from the World of Business. In: Zalmay M. Khalilzad und John P. White (Eds.): Strategic Appraisal. The Changing Role of Information in Warfare. Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 327–360.

Giles, Keir (2014): A New Phase in Russian Military Transformation, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies, 27 (1), 147-162.

Giles, Keir; Monaghan, Andrew (2014): Russian Military Transformation – Goal in Sight?, Carlisle: Strategic Studies Institute.

Gillespie, Paul G. (2009): Precision-guided Munitions and Human Suffering in War // Weapons of Choice. The Development of Precision Guided Munitions. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press.

Gormley, Dennis M. (2008): Missile Contagion. Cruisem Missile Proliferation and the Threat to International Security. Westport, Conn, Oxford: Praeger Security International.

Gormley, Dennis M. (2014): Sixty Minutes to Strike. Assessing the Risks, Benefits, and Arms. In: S+F 32 (1), 36–46.

Gormley, Dennis M. (2016): The Offense/Defense Problem: How Missile Defense and Conventional Precision-Guided Weapons Can Complicate further Deep Cuts in Nuclear Weapons (Deep Cuts Working Paper, 6).

Haas, Michael (2013): Die Weiterverbreitung fortgeschrittener Waffensysteme. edited by Christian Nünlist. Center for Security Studies (CSS). Zürich (CSS Analysen zur Sicherheitspolitik, 145).

Harknett, Richard J. and the JCISS Study Group (2000): The Risk of a Networked Military. In: Orbis, 44 (1), 127–143.

Heaston, R. J.; Valaits, V. K. (1989): Handbook of PGM Related Acronyms and Terms. Guidance and Control Information Analysis Center. Chicago.

Heaston, Robert J.; Smoots, Charles W. (1983): Introduction to Precision Guided Munitions. A Handbook Providing Tutorial Information and Data on Precision Guided Munitions (PGM). Chicago (1: Tutorial).

Hansel, Mischa; Ruhnke, Simon (forthcoming): A Revolution of Democratic Warfare? Assessing Regime Type and Capability Based Explanations of Military Transformation Processes; in: International Journal.

Hickey, James (2012): Precision-guided Munitions and Human Suffering in War. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Ltd (Military and Defence Ethics).

Hitchens, Theresa; Lewis, James Andrew; Neuneck, Götz (2013): The Cyber Index. International Security Trends and Realities. UNIDIR. New York and Geneva.

Horowitz, Michael C.; Fuhrmann, Matthew (2017): Droning on: Explaining the Proliferation of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. In: International Organization, 71 (2), 397-418.

Institute for Economics and Peace (2016): Global Peace Index 2016. IEP Report (39).

International Institute for Strategic Studies (2016): Military Balance. Arundel House, Temple Place, London, UK: Routledge for International Institute for Strategic Studies.

ITU: Cyberwellness-Profiles ITU. Acessed: http://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Cybersecurity/Pages/Country_Profiles.aspx.

Jasper, Ulla; Weiss, Moritz (2015): Konventionelle Bedrohungen, technologische Diffusion und die Entwicklung von militärischen Drohnen. In: Gabriele Abels (Ed.): Vorsicht Sicherheit! Legitimationsprobleme der Ordnung von Freiheit, Baden-Baden, Nomos, 219-237

Kaag, John; Kreps, Sarah (2014): Drone Warfare (Polity Press), Malden.

Kaushik, Mrinal; Hanmaiahgari, Prashanth Reddy (2017): Essentials of Aircraft Armaments. Singapore, s.l.: Springer Singapore (SpringerBriefs in Applied Sciences and Technology). Accessed: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2377-4.

Khalilzad, Zalmay M.; White, John P. (Eds.) (1999): Strategic Appraisal. The Changing Role of Information in Warfare. United States; Rand Corporation; Project Air Force (U.S.). Santa Monica, CA: RAND. Accessed: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=20486.

King, Anthony (2014): The Transformation of Europe’s Armed Forces: From the Rhine to Afghanistan, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Krebs. Gunter: Gunters Space Page. Accessed: http://space.skyrocket.de/directories/sat_c.htm.

Krepinevich, Andrew F. (1994): Cavalry to Computer; the Pattern of Military Revolutions. In: National Interest 37, 30–42.

Kubbig, Bernd W. (2005): Raketenabwehrsystem MEADS: Entscheidung getroffen, viele Fragen offen. Hessische Stiftung Friedens- und Konfliktforschung. Frankfurt (HSFK-Report, 10/2005).

Laird, Robbin; Mey, Holger H. (1999): The Revolution in Military Affairs: Allied Perspectives, Washington DC: Institute for National Strategic Studies.

Lewis, James A.; Timlin, Katrina (2011): Cybersecurity and Cyberwarfare. Preliminary Assessment of National Doctrine and Organization. UNIDIR.

Lewis, Michael; Sycara, Katia; Scerri, Paul (2009): Scaling Up Wide-Area-Search-Munition Teams. IEEE Computer Society.

Libicki, Martin (1996): The Emerging Primacy of Information. In: Orbis, 40 (2), 261–274.

Libicki, Martin C. (1999): Illuminating Tomorrow’s War. Washington, DC: Diane Pub Co (McNair paper, 61).

Loo, Bernard (2005): U.S. Military Transformation and Implications for Asian Security. Hg. v. Nanyang Technological University. Singapore (RSIS Commentaries, 39).

Major, Aaron (2009): Which Revolution in Military Affairs? Political Discourse and the Defense Industrial Base. In: Armed Forces and Society, 35 (2), 333–361.

Mandel, Robert (2004): The Wartime Utility of Precision Versus Brute Force in Weaponry. In: Armed Forces and Society, 30 (2), 171–201.

Mandel, Robert (2004): Security, Strategy, and the Quest for Bloodless War, Boulder, CO et al.: Lynne Rienner.

Mathers, Jennifer G. (2002): Reform and the Russian Military. In: Theo Farrell und Terry Terriff (Eds.): The Sources of Military Change: Culture, Politics, Technology, London: Lynne Rienner, 161-184

McDowell, Jonathan: Satellite list on Jonathan’s Homepage. Accessed: http://www.planet4589.org/space/.

Møller, Bjørn (2002): The Revolution in Military Affairs: Myth or Reality? Kopenhagen.

Mölling, Christian; Neuneck, Götz (2002): Informationskriegsführung und das Paradgima der Revolution in Military Affairs. Konzepte, Risiken und Probleme. In: Die Friedens-Warte, 77 (4), 375–398.

Müller, Harald; Schörnig, Niklas (2002): Mit Kant in den Krieg? Das problematische Spannungsverhältnis zwischen Demokratie und der Revolution in Military Affairs. In: Die Friedenswarte, 77 (4), 353-374.

Mulvenon, James C. et al. (2006): Chinese Responses to U.S. Military Transformation and Implications for the Department of Defense. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. Accessed: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=197629.

Murray, Scott F. (2007): The Moral and Ethical Implications of Precision-Guided Munitions. Air University Press, Maxwell Air Force Base. Alabama.

Neuneck, Götz (2012): Cyber War oder Cyber Peace? Wird das Internet zum Kriegsschauplatz? In: HSFK/BICC/FEST/IFSH (Eds.): Friedensgutachten 2012, Berlin: LIT Verlag, 136-149.

Neuneck, Götz; Alwardt, Christian (2008): The Revolution in Military Affairs, its Driving Forces, Elements and Complexity. Institut für Friedensforschung und Sicherheitspolitik (IFSH). Hamburg (IFAR Working Paper, 13).

Owens, William A. (2001): Lifting the Fog of War, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Persson, Mats; Rigas, Georgios (2014): Complexity: the Dark Side of Network-centric Warfare. In: Cognition, Technology & Work 16 (1), 103–115.

Raska, Michael (2011): RMA Diffusion Paths and Pattern in South Korea’s Military Modernization. In: The Korean Journal of Defense Analysis, 23 (3), 369–385.

Resende-Santos, J. (2007): Neorealism, States and the Modern Mass Army, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Resende-Santos, J. (1996): Anarchy and the Emulation of Military Systems: Military Organization and Technology in South America, 1870-1930. In: Security Studies, 5 (3), 193-260.

Ruhnke, Simon (2016): Die Rezeption der Revolution in Military Affairs und die Ursprünge der Vernetzten Sicherheit im deutschsprachigen Diskurs. In: Zeitschrift für Außen- und Sicherheitspolitik, 9 (3), 399–416.

Sauer, Frank (2014): Einstiegsdrohnen: Zur deutschen Diskussion um bewaffnete unbemannte Luftfahrzeuge, in: Zeitschrift für Außen- und Sicherheitspolitik, 7 (3), 343-363.

Sauer, Frank; Schörnig, Niklas 2012: Killer Drones: The ›Silver Bullet‹ of Democratic Warfare? In: Security Dialogue, 43 (4), 363-380.

Sayler, Kelley (2015): A World of Proliferated Drones. A Technology Primer. Center for New American Security. Washington, DC.

Schörnig, Niklas (2014): Liberal Preferences as an Explanation for Technology Choices: The Case of Military Robots as a Solution to the West’s Casualty Aversion. In: Maximilian Mayer, Mariana Carpes and Ruth Knoblich (Eds.): The Global Politics of Science and Technology: Perspectives, Cases and Methods (Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, 2014): 67-82

Schörnig, Niklas (2011): „Stell dir vor, keiner geht hin, und es ist trotzdem Krieg…“ – Gefahren der Robotisierung von Streitkräften. In: HSFK/BICC/FEST/IFSH (Eds.): Friedensgutachten 2011, Berlin: LIT Verlag, 355-366.

Schröder, Matt (2014): Fire and Forget. The Proliferation of Man-portable Air Defence Systems in Syria. Small Arms Survey. Geneva (Issue Brief, 9).

Schulzke, Marcus (2016): The Morality of Remote Warfare: Against the Asymmetry Objection to Remote Weaponry. In: Political Studies, 64 (1), 90–105.

Sechser, Todd S.; Saunders, Elizabeth N. (2010): The Army You Have: The Determinants of Military Mechanization, 1979-2001. In: International Studies Quarterly, 54 (2), 481–511.

Siouris, George M. (2004): Missile Guidance and Control Systems. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag New York Inc.

SIPRI: SIPRI-Trade Register. Online verfügbar unter http://armstrade.sipri.org/armstrade/page/trade_register.php.

Spivey, Mark W. (1999): Completing the Sensor Grid: A Revolution in Imagery Management. Naval War College. Newport.

Sugden, Bruce M. (2009): Speed Kills: Analyzing the Deployment of Conventional Ballistic Missiles. In: International Security 34 (1), 113–146. Accessed: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40389187.

Terriff, Terry; Osinga, Frans (2010): Conclusion: The Transformation of Military Diffusion to European Militaries, in: Terry Terriff, Frans Osinga and Theo Farrell (Eds.): A Transformation Gap? American Innovations and European Military Change, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 187-2010.

US Office of Outer Space Affairs: Outer Space Objects Index. Accessed: http://www.unoosa.org/oosa/osoindex/search-ng.jspx?lf_id=.

Valaitis, V. (1997): Handbook of Smart Weapon and PGM Related Acronyms and Terms 2nd Edition. Guidance and Control Information Analysis Center. Chicago.

Waltz, Kenneth (1979): Theory of International Politics (McGraw Hill), Boston, MA.

Way, Christopher; Weeks, Jessica L.P. (2014): Making It Personal: Regime Type and Nuclear Proliferation. In: American Journal of Political Science, 58 (3), 705–719.

Weiss, Linda (2014): America Inc.? Innovation and Enterprise in the National Security State (Cornell University Press), Ithaca, NY.

Zehfuss, Maja (2010): Targeting: Precision and the Production of Ethics. In: European Journal of International Relations, 17 (3), 543–566.

Military-Technical Transformation: Preparing an Index to Enable Comparative Research

Publications

Journal Articles:

Mischa Hansel and Simon Ruhnke (2017) A Revolution in Democratic Warfare? Assessing Regime Type and Capability-Based Explanations of Military Transformation Processes, in: International Journal, 72 (3), 356-379.

Mischa Hansel and Sara Nanni (2018) Quantitative Rüstungsanalysen im Zeichen von Digitalisierung und Automatisierung, in: Zeitschrift für Internationale Beziehungen, 25 (1), [Quantitative Armament Studies within the Context of Digitalization and Automation Processes].

Presentations:

Mischa Hansel and Simon Ruhnke: Military-Technical Transformation Index (MTTI): Assessing Competing Explanations and Conditions of Military Acquisitions, Colloqium Center for Security Studies, ETH Zürich, 2nd November 2017.

Mischa Hansel and Simon Ruhnke: Military-Technical Transformation Index (MTTI): Assessing Competing Explanations and Conditions of Military Acquisitions, 5. offene Sektionstagung der Sektion IB der DVPW, University of Bremen, 4th October 2017.

Mischa Hansel and Sara Nanni: Military-Technical Transformation Index (MTTI): Grundlagen für quantitativ-vergleichende Ursachenforschungen zur militärischen Transformation, Institut für Friedensforschung und Sicherheitspolitik an der Universität Hamburg (IFSH), 24th May 2017.

Mischa Hansel and Sara Nanni: Rüstungsdynamik beobachten? Herausforderungen für quantitativ-vergleichende empirische Forschungen zur militärischen Transformation [Observing Arms Dynamic? Challenges of Quantitative-comparative Empirical Research on Military Transformations], Tagung der DVPW-Sektion Internationale Beziehungen, Greifswald, 12th-13th January 2017.

Mischa Hansel and Simon Ruhnke: A Revolution of Democratic Warfare? Testing Liberal and Realist Explanations of Military Transformation Processes, 8th ECPR General Conference, Glasgow, 3rd-6th September 2014.

Mischa Hansel and Simon Ruhnke: A Revolution of Democratic Warfare? Introducing Fuzzy-Set Methodology to Discover the Driving Factors behind Military Transformations, International Studies Association Annual Convention, Toronto, 26th-29th March 2014.

Military-Technical Transformation: Preparing an Index to Enable Comparative Research

|

|

|

| Mischa Hansel | Sara Nanni | Marina Uebachs |

Military-Technical Transformation: Preparing an Index to Enable Comparative Research

Contact

Our project aims to fill a critical gap within studies on military transformation by providing a global database on military capabilities in advanced information technologies.We thus hope to facilitate more quantitative works on the causes and driving factors of military-technological diffusion processes. Comments and criticsm is therefore very much welcome.

Please direct all your inquiries to Dr. Mischa Hansel: mischa.hansel@ipw.rwth-aachen.de